International Law since 1945: A Personal Journey – Université de Zurich, 22.11.2007 (anglais)

Royaume-Uni

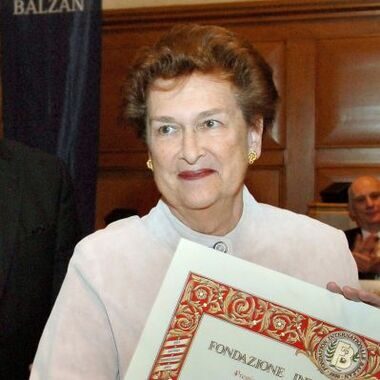

Rosalyn Higgins

Prix Balzan 2007 pour le droit international après 1945

Pour sa contribution fondamentale au développement du droit international à partir de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale ainsi que pour son activité scientifique, de juge et de présidente de tribunal; pour ses livres, ses recueils, ses articles et ses décisions juridiques, à la fois clairs et constructifs, novateurs et engagés pour la défense de l’état de droit et des droits de l’homme; pour son rôle de guide dans la consolidation et la diffusion du droit international moderne.

I am astounded to be standing here before you delivering an eve of ceremony Balzan Prize lecture.

As you may imagine, I am profoundly grateful to the Balzan Committee for this great honour.

I have had it explained to me by the Balzan Foundation that the tradition for an Award winner on the eve of the Award is to review his/her life and to present these ruminations as a lecture. I am anxious to comply with anything asked of me by those who have been so extraordinarily kind to me. But, a strict following of this injunction feels uncomfortably egotistical, and I think that what may be more interesting for my audience will be if I interweave some facts about my own life with the great developments that have occurred in my subject area since 1946.

This sort of exercise, with which I have been charged by the Balzan Foundation, inevitably leads me to a degree of introspection, not to say reminiscence. And, in proposing this lecture, I have come to see two things. First, I have had extraordinary good fortune in being in the right place, at the right time, to acquire an early expertise in important areas of international law that were then in their infancy. Second, I now realise that the intellectual worlds I have instinctively gravitated towards are those where the academic and scholarly overlap with the practical. I have always found institutions as important as the norms embraced by them. The norms embodied in the UN Charter can only be really understood if one is absorbed by how the various organs, committees, interest groups, really work.

So when in 1995 I came to the International Court of Justice, I came knowing rather a lot of court case law, but very little about its internal workings. I early became intrigued in “how” issues, finding them every bit as absorbing as the “what” issues. But this is to run ahead of myself and I mention it now merely to reinforce the intellectual attraction I have always felt in issues of process, as well as in substantive international law.

It is a common place to say that international law began with Grotius, Vitoria and Suarez in the16th and 17th centuries. But it is also true that the horrors of World War II and the establishment of the United Nations and its Charter in 1948 marked a new era in international law.

I studied law in the late 1950s at the University of Cambridge.

I was lucky enough in 1958, as I was just completing my legal studies at Cambridge, to be chosen as the United

Kingdom intern at the United Nations. This allowed me to participate in a programme where the selected intern would be assigned to the appropriate department for a period of training. I was assigned to the Department of Legal Affairs. The Head of that Department, Oscar Schachter, was known the world over as an exceptional international lawyer and a remarkable civil servant. His kindness to me was part of why I so early felt ‘at home’ at the United Nations. He was to become one of my very closest friends.

It has to be remembered that at that time the United Nations had been in existence for a mere 12 years. It was still possible for an eager student to get on top of much of what had been happening, legally and politically, in those first years. Thus it came about that when I was at Yale from 1959-61 for doctoral research, I embarked upon the topic of the Development of International Law by the Political Organs of the United Nations. This topic had been proposed to me by Eli Lauterpacht (now Professor Sir Eli Lauterpacht CBE QC), one of my Cambridge teachers. I take this opportunity of rendering in public my thanks to him (just as I have many times rendered my thanks in private) for putting me on to this theme. It immersed me in studying the world of the United Nations at a time when its size was such that the overall picture could be seen. It also allowed me to promote the idea that if we are to understand how international law is made, we must go beyond mere formalism and reiteration of the sources of law as listed in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice. It is not enough to say that international law is to be found in treaties, and in custom and judicial decisions; we have to appreciate how other bodies invoke legal norms and the manner in which that affects our understanding of them. Sometimes new international law is gradually formed by the constant reiteration, with subtle changes, of perceived new and necessary normative obligations.

So my doctorate was prepared under the joint direction of Oscar Schachter in the Legal Office of the United Nations in New York and of Myers McDougal, an inspirational teacher and scholar, at the Yale Law School. I endeavoured to show in that study that the Security Council and the General Assembly had in real life a major role in the affirmation and development of international law, notwithstanding that they were political bodies, and notwithstanding that they were neither conferences of states making treaties, nor judges pronouncing upon the law. This research was published in 1962 under the title of The Development of International Law by the Political Organs of the United Nations. Happily, it was well received, and my career in international law was kick-started.

Invitations to participate in conferences and give papers flowed on from that, and I could not believe that I was so welcome in this magical world of international law. There was never anything else I wanted to do (or, if the truth be told, would have been fit to do).

I cannot fail to mention the importance to me of Oscar Schachter and Myers McDougal. The first showed me that humanity and care for others should infuse all that one does professionally. The latter convinced me that law is not an abstract application of rules: it is a process directed towards the implementation of policy goals for the common good. These are lessons for life – they don’t get left behind at graduate school.

***

Another good stroke of fortune befell me in the mid-1970s. I was invited by Yale Law School to come for a semester, to teach the ‘core course’ on international law, but also to give another course of my own choosing. I had the feeling that the case law being gradually built up at Strasbourg was going to prove rather important. The European Convention on Human Rights had come into force for Council of Europe countries in 1970, and at that time both the Commission of Human Rights (later abolished in 1998) and the Court were hearing cases – individual applications against states (usually the national state of the applicant) and very occasionally inter-state cases. It was all intellectually exciting, but I knew I did not yet know this part of international law in the way I felt I understood United Nations law. I instinctively felt that it was time to add a further string to my bow. And this seemed realistic to me, as the quantum of Strasbourg case law (and scholarship on it) could still in 1975 be absorbed by a young academic.

So I determined to take this ‘European’ course with me to Yale, and set about immersing myself in this field. A by-product of this preparation was an article that was published in the British Yearbook of International Law on Derogations to Human Rights Obligations under Article 15 of the Convention. When a decade later I was to serve as the United Kingdom member of the Committee on Human Rights, under the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, this immersion in the legal world of human rights undertaken, and sometimes then qualified, or later derogated from, was to stand me in good stead.

My own time on the Human Rights Committee – the quasi judicial and monitoring body established under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights – began in 1985. It was my first assignment at the invitation of my government and my first exposure to elections in the United Nations. The Committee on Human Rights had – and still has – a high reputation for independence and integrity, and in its work politics was held firmly at bay. And it was a body entering an exciting period of institutional development. Among other things, developments in the case law on novel legal issues were occurring with important frequency. The writing by the Committee of so-called General Comments was just under way. This is the device by which, even without waiting for an issue to arise in a claim made under the Optional Protocol, upon which the Committee could then pronounce, it will rather pro-actively draft an authoritative interpretation of a provision of the Covenant, as a guide to State Parties thereto.

During my time there the Committee drafted the famous – or infamous, depending on your view – General Comment No. 24. I was much involved. This General Comment concerned reservations made by States to the Covenant. The prevalent interpretation of the rules enunciated by the ICJ in 1951 and then refined in 1969 in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties for States was that the acceptability of reservations to a treaty depended on other states’ objections to the reservations made. This would determine what obligations were in force between those states. A reservation to an obligation would be not force as between two states where one state had formally objected to such a reservation. This classic rule of the law of treaties has proved singularly ill-suited to human rights treaties including the Covenant and the First Optional Protocol. As the Committee noted, “Although treaties that are mere exchanges of obligations between States allow them to reserve inter se the application of rules of general international law, it is otherwise in human rights treaties, which are for the benefit of persons within their jurisdiction.”[1] In the absence of sovereign interests, States had shown little interest in objecting to the large numbers of disturbing reservations being made by others to human rights treaties. The Committee thus found that the responsibility fell on it to determine the compatibility of a reservation with the object and purpose of the Covenant.[2] The Committee therefore analysed the object and purpose of the Covenant (and the First Optional Protocol) and identified the kinds of reservations that would be legally problematic. For example, “reservation to article 1 denying people the right to determine their own political status and to pursue their economic, social and cultural development, would be incompatible with the object and purpose of the Covenant”. The Committee also recommended, inter alia, that States “should institute procedures to ensure that each and every proposed reservation is compatible with the object and purpose of the Covenant.”[3]

The issue of reservations to human rights treaties has occasioned much comment. A much voiced perception as the International Law Commission began work on this topic in 1993 was that the “real law” was as stated by the ICJ in 1951 in the Advisory Opinion on Reservations to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide[4] and that the work of the Human Rights Committee resulting in General Comment 24[5], along with the Judgments on reservations of various human rights courts and tribunals that departed from this approach, were thus merely aberrations.

But the Court in 1951 had been answering only the specific questions put to it by the General Assembly. Since 1951 many issues relating to reservations have emerged, including whether a role as regards assessment of compatibility with object and purpose is to be assigned to monitoring bodies (such as the Committee on Human Rights) established under multilateral human rights treaties and the Advisory Opinions issued by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights[6]. The Human Rights Committee’s analysis of these problems in the context of the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights has been very close to that of these great regional courts. The practice of such institutions – for example, the European Court of Human Rights with the Belilos[7] and Loizidou[8] cases is not to be viewed as “making an exception” to the law as determined by the ICJ in 1951. The Judgment in 1951 was never so confined and developments are occurring to meet contemporary realities.

Today it is clear that the 1951 Advisory Opinion should not be read in such a restrictive way. In the recent Congo v. Rwanda case, in the International Court of Justice, the impact of Rwanda’s reservation to Article IX of the Genocide Convention was in issue.[9] The Court found that Rwanda’s reservation was not incompatible with the object and purpose of the Convention. The Court’s finding on this went beyond noting that a reservation had been made by one State, which did not occasion an objection by the other. The Court added its own assessment of the reservation’s compatibility.

This summer, at the meeting of its 59th session, the ILC adopted a number of draft guidelines, including Draft Guidelines 3.1.12, “Reservations to general human rights treaties.” These suggest criteria for assessing the compatibility of reservations to Human Rights treaties. So this seems to mark a step forward, and a leaving behind of old entrenched positions.

There is now an immense jurisprudence on all these matters, civil and political rights, and the extent to which and the circumstances in which they may be limited. A major contribution has been made by the European Court of Human Rights, the guarantor of the European Convention on Human Rights. From 1998 till January 2007 the Presidency of this most important Court was in the hands of Luzius Wildhaber, and the significance of what the Court achieved in those years cannot be exaggerated. For this and many other reasons I am honoured that he is my Chairman tonight.

Throughout this period I was teaching a Masters’ Course on Human Rights Law at London University, with the late, brilliant, Peter Duffy, who died much too young. The seminars were bursting at the seams, but I never restricted the entry numbers, because students wanting to learn about human rights should only be encouraged to do so. We resolutely did not lecture, but taught socratically (albeit in a very structured way), engaging the students. The students emerged from that course knowing that opinions without the underlying knowledge are worthless; knowing the case law of the European Convention on Human Rights under all the major provisions of the Convention and its protocols, and of the Committee on Human Rights under the Covenant provisions. And they were immersed in the great doctrinal debates raging at the time, including that of so-called ‘cultural relativity’ in regard to human rights. I think they left understanding that ‘cultural relativity’ is the cry of governments rather than of the oppressed: the basic freedom from fear and abuse are wanted by all of humankind, regardless of race or religion. I have written extensively about these and related human rights matters and it gives me comfort that I see so many of my former students – including those who studied human rights law with me – today in high positions in their own countries.

***

I had come back from the UN with a fair understanding of this rather new institution, the people in it and how it worked. In 1956, just before I went there as a pre-doctoral intern, the UN had engaged in its first real peacekeeping action, the UN Emergency Force in Egypt, set up after the military intervention in Suez.

The Charter envisaged that States could reasonably be required to abstain from the use of force save in self-defence through the provision of collective security by the Security Council. Article 39 empowers the Security Council to determine the existence of a threat to or breach of international peace, and to recommend or decide on measures to maintain or restore international peace. Article 40 provides for provisional measures. Article 41 refers to non-forcible sanctions including diplomatic and economic sanctions. Article 42 provides for military enforcement measures, to be carried out by forces made available to the Security Council under the special agreements envisaged in Article 43. The Security Council would thus be able to order economic and diplomatic sanctions, and also – directly, if it so chose, without first imposing sanctions under Article 41 – military sanctions. The forces would be available, the decision to use them in particular circumstances binding on all concerned. The Military Staff Committee was to be established to deal with the military planning and logistical aspects of such measures, as well as advising on a number of other military matters contained in Articles 45-47 of the Charter.

But the reality has been otherwise. The UN failed, largely because of the Cold War, to put in place this envisaged collective security system.

A consequence was that the United Nations decided that the absence of agreements under Article 43 made impossible an obligatory call upon members to participate in military enforcement. But military interposition, upon the request of the receiving State, and with the participation of those members of the United Nations which volunteered, would be possible. Thus was the notion of UN peacekeeping born. In 1957, with the United Nations Emergency Force in operation, Dag Hammarskjöld issued his famous Summary Report of 1958, which was to operate as a model for peace-keeping operations for the next thirty five years. Central to those understandings were that peace-keeping would be by consent; that force would be used only in self-defence (later, in the Cyprus operation – coming after the difficulties of the UN operation in the Congo – this was extended to force to protect the integrity of the mandate and agreed freedom of movement); and that it would not be used to determine political outcomes within a country.

These were the products of legal creativity that I sought to explain and analyse in my peacekeeping volumes. When I took up my very first job, as the staff international lawyer at the Institute of International Affairs, my early exposure to the UN meant that I was thus in a position to be able to embark upon a four-volume study on UN Peacekeeping, covering these activities as they were unfolding in the Middle East, Africa, Europe and Asia. Throughout the volumes I used a template , that I applied to each and every operation then existing: the background, the enabling resolutions, the function assigned, relations with the host state, with the contributing states, with UN member states generally, financial issues, and the implementation of the mandate. Since then, peacekeeping has gone through many models, in about 60 countries, in circumstances of great legal and political complexity. Others must work on the legal problems of these many examples (though I continued some writing in the area, especially on the Balkans peacekeeping, until I became a Judge). But it seems that the template and analysis of my four volumes are still regarded as helpful; and naturally I am glad of that.

At the beginning of the sixties, the leading actors in the world of international law were mainly – with a few exceptions – the developed States of the world, the “old” States. That decade marked the coming on to the stage of many newly independent countries, particularly from Africa, and the world of international law has never been the same again.

There was scepticism, indeed almost hostility, among this community of new States as to whether international law was a law relevant to their interests as well as to the interests of the so-called first world. At the same time, the longer established States wanted to feel secure that international law would continue to provide a core stability that would be applicable to all nations.

It is easy today to forget that the sixties was characterised by a period of intense North-South tension in which many of these new States did not trust the institutions of international law, feeling that international law was a law that had not been made by them. But they rapidly came to appreciate that they could be significant players both in treaty-making and in the refinement of custom. It took less than two decades for these States to become adept at using the General Assembly of the United Nations for promoting changes to existing law and introducing new concepts that reflected their aspirations. Many of these new ideas ultimately finished up as General Assembly resolutions.

Resolutions of the General Assembly are not binding, but they can have an important impact on the development of customary international law. In the Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat of Use of Nuclear Weapons, the International Court noted that:

General Assembly resolutions, even if they are not binding, may sometimes have normative value. They can, in certain circumstances, provide evidence important for establishing the existence of a rule or the emergence of an opinio juris. To establish whether this is true of a given General Assembly resolution, it is necessary to look at its content and the conditions of its adoption; it is also necessary to see whether an opinio juris exists as to its normative character. Or a series of resolutions may show the gradual evolution of the opinio juris required for the establishment of a new rule. (para. 70).

In the sixties, the idea of self-determination as a legal, rather than a political, concept was novel. The General Assembly and the ICJ played a significant role in this transformation. The legal tools for peacefully ending colonialism were forged. And then great battles were fought over what was then termed by the one side as “economic colonialism” and by the other as the need for stability and protection of international investment. One of the most significant resolutions in this early period was Resolution 1803 (1962), the Declaration on Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources. This Resolution declared inviolable the right to permanent sovereignty over natural resources and the right to nationalize or expropriate on the grounds of “public utility, security or the national interest”. It also laid down the legal obligation for the payment of “appropriate compensation” – a departure from the classical formula of “adequate, promote and effective compensation”. It is hard to recall how bitter the battles were. The concept of Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources was later reaffirmed in the International Covenants on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and on Civil and Political Rights of 1966, and subsequent General Assembly resolutions, namely, Resolution 3201 (1974), the Declaration on the Establishment of a New International Economic Order, and Resolution 3281 containing the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States, radicalised the concept further. By the late eighties, a largely effective consensus had emerged, essentially reflecting the original 1803 Resolution – but not the later more radical Resolutions. We see these new international law norms applied each week by arbitral tribunals and by the US-Iran Claims Tribunal.

It was against this background that the great international petroleum concession arbitrations were occurring, with the tensions there reflected between long term overseas investors from the developed states, and states in the resource-rich developing world feeling the need to change contractual arrangements entered into either by the prior colonial state or by themselves at the outset of their independence. It was challenging enough to perceive trends and patterns in these rapidly evolving developments – exactly at that crossroads of law and politics that had always interested me. But at the very same time North Sea Oil was beginning to come on stream. From the practitioner’s point of view, an era was beginning, in which much of the legal practice would be “built up with events”. 1972-1980 was a period of remarkable activity in law development about property rights in petroleum licences, governmental consents, the legal status of rigs, revocability, production flow controls, and so on and so forth. I was advising a major international oil company during this period in its negotiations with the UK government and with the government-established British National Oil Company. It is hard to describe the intellectual excitement of that era – we all felt, on all sides, pioneers in a great venture and in an emerging corpus of UK Law and International Law. There was established an International Bar Association Committee – in which I was very active – for energy law. I started an LLM course on the international law of natural resources, in which students could study both natural resource issues in the developing world (and the relevant case law) and the emerging legal regime in the North Sea. It was salutary for them to see that how a state behaved as an exporter of capital was not always the same as when it was importing capital needed for the production of its own natural resource. A student, a counsel, a judge: all have to understand how things might look ‘from the other side of the fence’. This LSE course, together with the Energy Law courses being given at Dundee University, were the only ones of their kind in the country. The Dundee Centre for Energy, Petroleum and Mineral Law and Policy has since then developed into a world leader in education and research in energy law and policy, under the exceptional leadership of Professor Thomas Walde.

I so enjoyed the occasions each year (and I think the students did, too) when the young activists of my human rights course and the potential corporate lawyers of my petroleum law course met together in a joint seminar, to discuss natural resources and indigenous peoples. Then they really were forced to think about how issues looked ‘from the other side of the fence’. As well as practicing in Petroleum Law, I enjoyed practicing, in the English and various international courts, on a range of international law issues. I’ve pleaded as counsel before the European Court of Human Rights, the Court of Justice of the European Communities, and the International Court of Justice. And in the English courts, I did a fair amount on issues of diplomatic and state immunity and was involved in some of the leading international law cases of the time. At the top of the list, I suppose, would be the cluster of cases that arose from the collapse of the International Tin Council, an international organization established within the UN System. I had the great good luck to be asked by the International Tin Council to act for them on all international law matters. There were cases in the Chancery Division, cases in the Queen’s Bench Division, cases in the Court of Appeal, and cases in the House of Lords. It was an exhilarating and exhausting experience.

***

In 1993 I was honoured to be invited by the Curatorium of the Hague Academy to deliver the 3-week long General Course in International Law. I had in 1986 given a shorter course on The Taking of Property by the State. The General Course is not a definitive treatise on the entirety of international law; it is rather a personal statement on the ideas underlying international law, illustrated as one chooses.

I began the course with these words “International Law is not rules. It is a normative system”.

Later I commented that international law is a normative system characterised by being “harnessed to the achievement of common values – values that speak to us all, whether we are rich or poor, black or white, of any religion or none, or come from countries that are industrialised or developing”. In the book of these lectures, Problems and Process, I sought to show that there is an essential and unavoidable choice to be made between the perception of international law as a system of neutral rules, and international law as a system of decision-making directed towards the attainment of certain declared values. I deliberately wrote about many of the difficult and unanswered issues in international law today – how we balance needed immunities with the rejection of impunity; how we allocate jurisdictional competences in an increasingly interdependent world; how sovereignty over deposits of natural resources can be made compatible with global needs, etc. And I endeavoured to demonstrate that the acceptance of international law as process leads to certain preferred solutions so far as these great unresolved problems are concerned.

***

Thus as my life stood in 1994, I was a full time Professor at London University, teaching one undergraduate and four specialist Masters’ Courses out of the London School of Economics Law Department as well as doing all the usual academic writing, marking of exams, doctoral supervision and administration that always goes with a Chair; I was also heavily engaged in legal practice at the English Bar and before various International Courts; and I was spending three months a year on work for the UN Committee on Human Rights. I haven’t mentioned my infinitely patient husband and my children in this recitation of why I sorely needed days that contained more than 24 hours in them.

Then came my nomination to the International Court of Justice, and after I was elected in 1995 I suddenly found that I was doing a single job, instead of four. The brick walls outside my window at the LSE were replaced by extensive views over gardens and water. We have a wise tradition at the Court that we do not write or speak – save in a passing and descriptive way – about the cases we have decided: “The Judgment must speak for itself”. I have continued to write articles and to give speeches, but now almost invariably centred on the work of the Court generally, or issues relating to the Court (including court procedures and management).

Some past loves of my life have had to be left behind. I can no longer be involved in the exciting developments in petroleum law, nor investment dispute arbitrations. Some other topics I thought had gone for ever – such as immunities from suit and execution – but the Court has recently started seeing cases in which these issues arise. It used to be the case that if a state thought it was immune from suit or other legal process in the courts of another, it would instruct counsel to appear in the courts of that state to challenge jurisdiction. I used to do such cases in the old days. This appearance to challenge jurisdiction is not, of course, a waiver of immunity. Recently, however, there has been a tendency for states not to follow this time-honoured path, but rather to come immediately to the International Court of Justice to claim that its sovereignty has been violated by the attempts of the courts of the forum to exercise jurisdiction. The Arrest Warrant Case of 2002 is now being followed by the forthcoming cases between Congo v. France and between Djibouti v. France. We will be hearing this latter case early in the New Year. In all of these such contentions are at issue.

It seemed in 1995 that my prolonged involvement with human rights law must also necessarily be at an end. The Court, after all, was not a specialist human rights court. Further, the Statute of the Court permits only States as litigants before it, and the great explosion in human rights case law has arisen through complaints by individuals against governments, often their own.

From the years 1995 till early 2006, I served on the Rules Committee of the Court, and as the Chairman in the last three years. This Committee not only proposes periodic changes to the Rules of Court (usually in the light of experience from cases that have been heard in the Court), but it has the mandate to oversee the judicial efficiency of the Court generally. In the Oxford Blackstone Lecture of 1999 I deployed some of the challenges facing a Court whose clients are sovereign states. I think the Court has made significant progress in tightening its procedures. In 2001 we introduced Practice Directions, a means by which we tell states (and counsel) appearing before us what we expect of them in particular circumstances. For example, we specify what must be shown for the Court to choose to exercise its power when the Statute admits a late document; we elaborate (as we found necessary in the new world of the Internet) what we mean by a document being “in the public domain”; we indicate what we do and don’t want to find within the “Judges’ Files” presented to us by the parties to assist in the presentation of their oral pleadings. We are finding that States using us now understand that some curtailment as to time allowed, documents admitted etc., not only speeds along their own case but is also helpful to other states waiting in the queue for their case to the heard.

The main task of the international judge is to contribute to the Judgment of the Court. At the International Court we have a very inclusive way of working, not using, for example, Juges-rapporteurs or Advocates General. Occasionally, I have felt it important to write a separate opinion and even more rarely, a dissenting opinion. These opinions have necessarily dealt with diverse points of law. What I hope is a common thread in them is the commitment to transparency in judicial decision-making, to the importance of showing that the Court has indeed understood and answered the arguments of counsel, and finely balanced issues are to be decided by open reference to the policy considerations of stake in the judicial choices made. Law is not an automatic application of rules. It is about the process of making authoritative decisions, – and sometimes choices between plausible propositions – for the common good.

The International Court is the principal judicial organ of the United Nations.

The International Court has a dual role: to settle in accordance with international law the legal disputes submitted to it by States, and to give advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by the organs of the United Nations and 16 duly authorised specialized agencies.

From 1946 to the present date, the Court has decided some 94 cases. Some one-third of those have been handed down in the last 10 years.

The States who are using the International Court include the ‘traditional clientele’ such as the United States, France, Germany, the United Kingdom and Spain. But States from what was Eastern Europe, from Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East have also appeared before the Court. Our cases come from all over the world: our docket presently contains three cases between Latin American States, three between European States, two between African States, one between Asian States and two of an intercontinental character.

The subject matter of cases coming to the International Court has also been changing. The ‘classical’ topics of boundaries, sovereignty, maritime delimitation still come to the Court. But so do now a variety of ‘cutting edge’ issues, such as the scope of self defence, pursuit of trans-boundary attacking groups into their territory of origin, the applicable Geneva Convention law in circumstances of extended occupation, the concept of occupation in a part of territory, immunities of state officials, genocide. The Court is busier than ever, and the diversity of those states using it affirms that it is truly the Court of the United Nations.

It is a privilege beyond compare to be entrusted with the presidency of the International Court. A president must maintain all that is already excellent in a court, and do yet more – institutionally and substantively – before leaving office. Just as eternal vigilance is the price of liberty, so is the maintenance of the impartiality and high quality of the Court’s Judgments and Opinions. And we must at the same time modernize and communicate.

As I reported to the General Assembly three weeks ago, the Court has this past year taken on a remarkably heavy programme of cases in an effort to provide the best service possible to the states visiting it. We have an active programme in place to maximise our contacts with other courts – our friends – in an atmosphere of mutual respect. Cooperation and understanding is the best way to avoid the pitfalls of unnecessary fragmentation in international law.

I do take the awarding of the Balzan Prize as an acknowledgement of the contribution of the International Court since 1946, to the purposes stated in the Charter of the United Nations : the maintenance of peace and security. Its particular contribution is the judicial settlement of international disputes in conformity with the principles of justice and international law. Through this Award given to the person who happens to be President of the Court, I am deeply grateful to the Balzan Foundation for having recognised the continuing pivotal role of the Court in the field of international law.

[1] Human Rights Committee, General Comment 24, Issues relating to reservations made upon ratification or accession to the Covenant or the Optional Protocols thereto, or in relation to declarations under article 41 of the Covenant, (Fifty-second session, 1994), UN Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.6 (1994), at 8.

[2] Id. at 18.

[3] Id. at 20.

[4]Reservations to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Advisory Opinion of 28 May 1951, [1951] ICJ Rep. 15.

[5] Human Rights Committee, General Comment 24, Issues relating to reservations made upon ratification or accession to the Covenant or the Optional Protocols thereto, or in relation to declarations under article 41 of the Covenant, (Fifty-second session, 1994), UN Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.6 (1994).

[6] The Effect of Reservations on the Entry Into Force of the American Convention on Human Rights (Arts. 74 and 75), Advisory Opinion OC-2/82 of 24 September 1982, IACHR (Ser. A) No. 2; Restrictions to the Death Penalty (arts. 4(2) and 4(4) American Convention on Human Rights), Advisory Opinion OC-3/83 of 8 September 1983, IACHR (Ser. A) No. 3.

[7] Belilos v. Switzerland, Decision of 29 April 1988, [1988] ECHR (Ser. A).

[8] Loizidou v. Turkey, Decision of 18 December 1996, [1996] ECHR (Ser. A.)

[9] Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo (New Application: 2002) (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Rwanda), Preliminary Objections, Judgment of 3 February 2006 (not yet published).